Immigration policy is the way the government controls via laws and regulations who gets to come and settle in Canada. Since Confederation, immigration policy has been tailored to grow the population, settle the land, and provide labour and financial capital for the economy. Immigration policy also tends to reflect the racial attitudes or national security concerns of the time which has also led to discriminatory restrictions on certain migrant groups. (See also Canadian Refugee Policy.)

(This is the full-length article on immigration policy in Canada. If you wish to read a plain-language summary, please see Immigration Policy in Canada (Plain-Language Summary).)

June 1947

Several federal government departments or agencies have been responsible for immigration policy since the Second World War: the Ministry of Mines and Resources (1936-1949), the Department of Citizenship and Immigration (1950–66, 1992–2016), the Department of Manpower and Immigration (1966-77), and the Canada Employment and Immigration Commission (1977–1992). Since 2016, immigration is primarily the responsibility of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC).

Under the British North America Act, constitutional responsibility for immigration is divided between the provincial and federal governments. However, for most of Canada's history, Ottawa has dominated this policy area, although Ontario since the Second World War, Quebec since the mid-1960s, and British Columbia since 2010, have been particularly concerned with immigration. As of 2017, all provinces and some territories have agreements with Ottawa allowing them to select and recruit immigrants based on their social and economic needs. Quebec is, however, by far the province who exercises the most autonomy in the field of immigration policy.

Quebec created its own department for immigration in 1968. Its major concerns have been to recruit as many French-speaking immigrants as possible to the province, and to ensure that immigrants who settle in Quebec form part of the francophone community. Quebec was the first province to have a special immigration agreement with the federal government. The federal government is also involved in the task of increasing the numbers of French-speaking immigrants to Canada. (See also Quebec Immigration Policy.)

In recent years every province (except Québec, which has its own, similar scheme) has established a Provincial Nominee Program, allowing provincial governments to nominate specific immigrant applicants, with the requirement that they reside for a period of time in that province. Although the programs vary from province to province, they generally have two goals – to boost population growth, and to recruit immigrants with desirable job skills, or language skills, into a province's workforce. Some programs allow immigrants to fast-track their applications for entry into Canada. About 51,000 immigrants (out of a total of approximately 300,000) were expected to become permanent residents in Canada through Provincial Nominee Programs in 2017.

In the 19th century, the movement of individuals and groups to Canada was largely unrestricted. This mostly “open door” policy encouraged white immigration to Canada and notably the settlement of Western Canada. (See also Immigration in Canada.)

Canada was, however, not open to all. The first Immigration Act passed in 1869 and specifically discriminated against people on the grounds of class and disability. Immigration was also discriminatory on the basis of race. In 1885, under pressure from British Columbia, the federal government imposed policies to restrict Chinese immigration like a head tax and, later on, the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923. These explicitly racist measures directed at the Chinese continued until the late 1940s.

Even white migrants were discriminated on the basis of their ethnic backgrounds: Anglo-Saxon settlers from Britain and the US were seen as the best fit whereas Italians and Greeks were viewed as harder to assimilate and therefore less desirable.

An advertisement from 1923 for the "Pittsburgh" that traveled between Belfast Northern Ireland and Canada.

After large cohorts of mostly European immigration came to Canada between 1903 and 1913, and a series of political upheavals and economic problems that followed the First World War (see Winnipeg General Strike), a much more restrictive immigration policy was implemented.

Under a revised Immigration Act in 1919, the government excluded certain groups from entering the country, including Communists, Mennonites, Doukhobors and other groups with particular religious practices, and also nationalities whose countries had fought against Canada during the First World War, such as Austrians, Hungarians and Turks.

The federal government also applied increasingly arbitrary restrictions on the basis of race and religion. In 1911 the government considered banning Black immigrants, but ultimately did not follow through with the idea. Arbitrary restrictions on South Asian migration to Canada in the early 20th century culminated in the events surrounding the passengers of the SS Komagata Maru who challenged these discriminatory and exclusive policies. In 1939, Jewish refugees fleeing from Nazi Germany abord the MS St. Louis were denied entry into Canada on arbitrary grounds related to their Jewish backgrounds.

Many of these discriminatory policies and practices continued until the middle of the 20th century.

Canada's restrictive immigration policies began to slowly and gradually ease after the Second World War, partly thanks to booming economic growth (and demand for labour) and partly due to changing social attitudes.

Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Photo taken on: October 11th, 2013

In 1947 the formal ban on Chinese immigration was ended. However, in 1952, a new Immigration Act maintained Canada's discriminatory policies against non-European and non-American immigrants. It was not until in 1962 that the federal government ended racial discrimination as a feature of the immigration system. In 1967, a points system was introduced to rank potential immigrants for eligibility. Race, colour, or nationality were not factors in the new system; rather, work skills, education levels, language ability (in speaking French or English), and family connections became the main considerations in deciding who could immigrate.

In 1969, Canada signed the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. Despite recognizing refugees as a special humanitarian class of migrants, Canada created no formal measures for examining refugee claims – continuing as in the past only to admit refugees on a case-by-case basis. (See Canadian Refugee Policy.)

Immigration and population policies were overhauled substantially in 1975. After substantial consultation, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau passed a new Immigration Act, 1976.

The Act, which took effect in 1978, was a radical break from the past. It established for the first time in law the main objectives of Canada's immigration policy. These included the promotion of Canada's demographic, economic, social, and cultural goals, as well as the priorities of family reunion, diversity, and non-discrimination. The Act also enabled co-operation among levels of government and the volunteer sector in helping newcomers adapt to Canadian society. For the first time, the Act also defined refugees as a distinct group of immigrants in Canadian law, requiring the government to meet its obligations to refugees under international agreements.

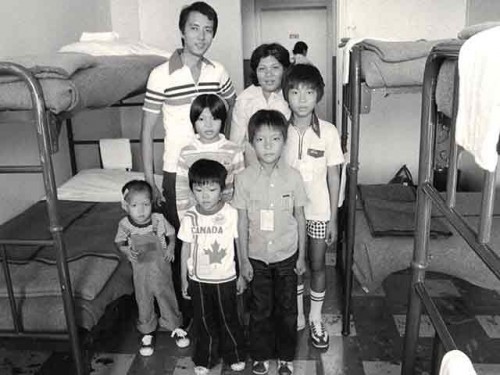

Griesbach Military Base in Edmonton, one of the arrival points for Southeast Asian refugees.

In 1979, Canada embarked on a unique program allowing private groups (most often churches and ethnic community organizations) to sponsor refugee individuals or families, bring them to Canada as permanent residents, and assist them in settling here. As of 2017, the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program has settled more than 275,000 people in Canada – over and above government-assisted refugees. Despite the program's success, it has been criticized in recent years for cumbersome paperwork and delays, and for growing restrictions on where refugees can be sponsored from. (See Canadian Refugee Policy.)

The Act broadened who has a role in shaping policy and establishing annual immigration levels. It gave provincial governments, ethnic groups, and humanitarian organizations the opportunity, through consultations with the federal government, to have their views heard by federal immigration officials.

The Act also modernized how refugee status is determined in relation to national security and enforcement. And it set out that the quasi-judicial Immigration Board (originally created in 1967) should be a fully independent body whose decisions on immigration claims and appeals cannot be overruled by government, except in relation to security matters.

By 1980, five classes of immigrants had been established for entry to Canada: Independent (people applying on their own); Humanitarian (refugees and other persecuted or displaced people); Family (having immediate family already living in Canada); Assisted Relatives (distant relatives, sponsored by a family member in Canada); and Economic (people with highly desirable employment skills, or those willing to open a business or invest significantly in the Canadian economy).

By the 1990s, after decades of legal and administrative reform, the racial make-up of immigrants was also changing. Asia (particularly China, India and Philippines) had replaced Europe as the largest source of immigrants to Canada.

During the 1980s, policy makers instituted a program to encourage business people and entrepreneurs to immigrate to Canada, bringing their managerial skills and financial capital in order to create additional employment opportunities. Many immigrants have since brought substantial capital and jobs to Canada. Without more immigration, the decline in fertility in Canada in the 21st century would create important social challenges. With fewer working-age Canadians, it would be difficult to shoulder the cost of health and social programs for the increased number of elderly citizens. In addition to increasing the workforce, immigration also supplements the needs of a modern economy for education and skills. As such, Canada continues to favour highly skilled and educated immigrants. In 2018, economic class entrants were the single largest category of immigrants, making up 186,352 of the 321,035 total immigrants admitted that year. The practice of admitting highly skilled people from less-developed countries continues to provoke some controversy. The governments of the developing countries, from which a growing number of immigrants to Canada originate, regard with apprehension the exodus of people they can ill afford to lose. While the view has been expressed that Canada should not encourage the outflow of trained individuals from "have-not" regions of the world, Canada stoutly defends the concept of freedom of movement for all persons.

In 2001, after the September 11 terrorist attacks on the United States, Canada replaced its 1976 Immigration Act with the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. The new Act, which came into force in 2002, maintained many of the principles and policies of the previous one, including the various classes of immigrants. It also extended the family class to include same-sex and common-law relationships. (See Family Reunification in Canada.)

Most importantly, the 2001 Act gave the government wider powers to detain and deport landed immigrants suspected of being a security threat. In 2004, Canada and the US banned the practice of allowing migrants to enter one country on a travel visa and claim refugee status at the border of the other via the Canada-United States Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA). However, this policy has been criticized with many critics arguing that the US is not a “safe third country” for migrants because of the US’ more hostile approach with migration. (See Canadian Refugee Policy.) Some asylum seekers bypassed the STCA by doing irregular border crossings to claim asylum in Canada. In 2023, the agreement was renegotiated to limit this loophole.